In the moment of the COVID-19 pandemic we are living, we sometimes hear concerns about the efficacy of vaccines. One of the reasons argued against vaccination is that among infected with COVID-19 there is more vaccinated than unvaccinated people. The aim of this post is to show that as more people receive effective vaccines, the proportion of vaccinated among infected people will also increase.

Let’s suppose that we have a population of one million in a region where a fraction of 10% is infected with COVID-19 when not vaccinated. This means that with no vaccination we have 100,000 people infected.

Let’s introduce a vaccine with an efficacy of 80%. This means that 80% of the people that would be infected without the vaccine will get rid of the disease if vaccinated. So, if only 20% out of 10% will be infected, the vaccine reduces the infection rate from 10% to 2% for the vaccinated.

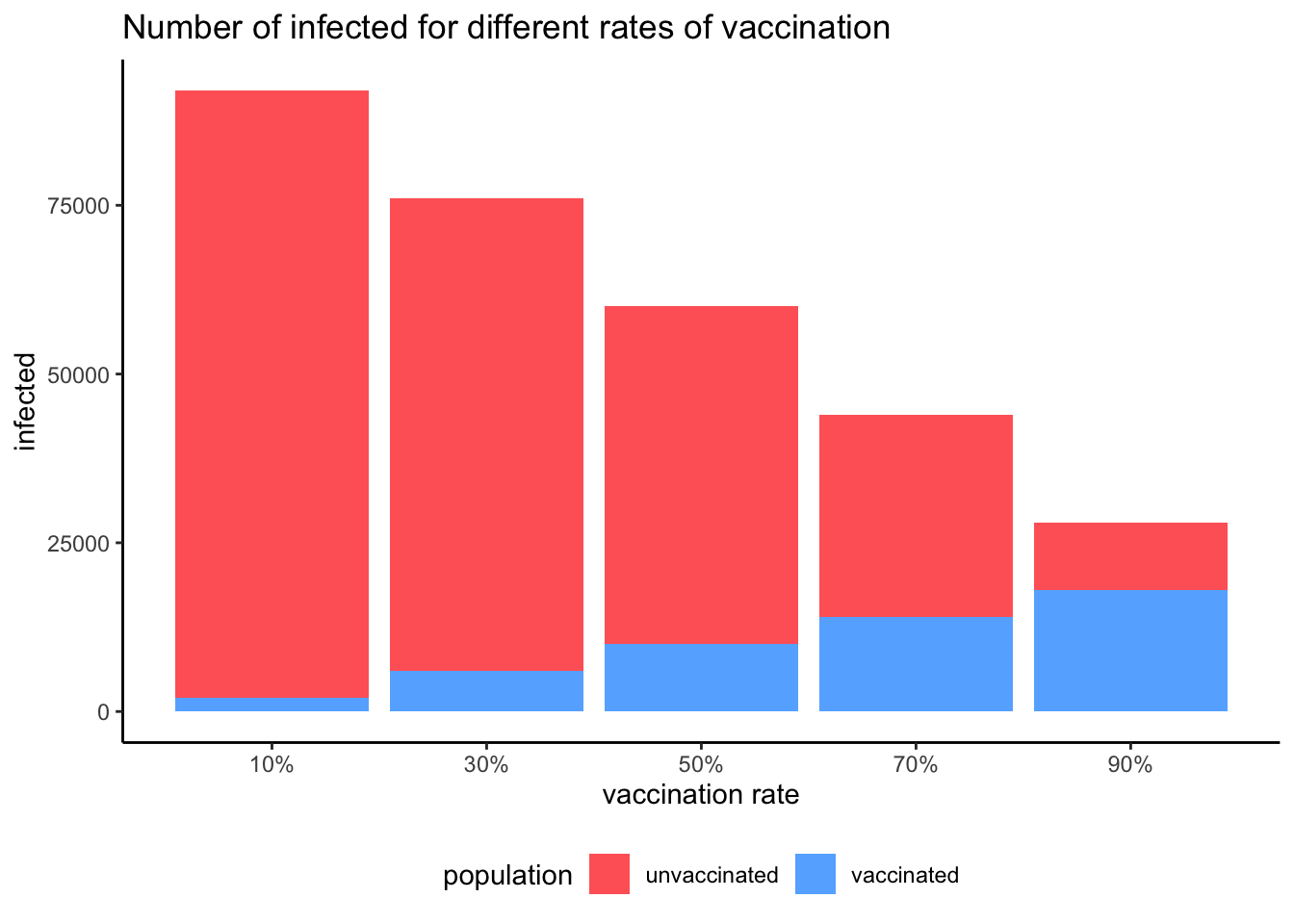

When we have the 30% of the population vaccinated, we can expect 70,000 (10% out of 700,000) of infected among the unvaccinated. Among the 300,000 vaccinated, we will have only 6,000 people infected (the 2% of 300,000). So we have 70,000 + 6,000 = 76,000 people infected.

What happens when the vaccination rate raises to 70%? We can expect 30,000 infected among the 300,000 unvaccinated, but only 14,000 out of the 700,000 vaccinated. So we have now 30,000 + 14,000 = 44,000 people infected. There are less people infected now, but the proportion of vaccinated among infected raises to 31.8%.

With a vaccination rate of 90%, we have only 10,000 infected among a population of 100,000 still unvaccinated, and 18,000 infected among the 900,000 vaccinated. We have now 10,000 + 18,000 = 28,000 infected. Now the 64% of infected are vaccinated people.

In the chart below I am presenting how is evolving the number of vaccinated and unvaccinated infected as the coverage of the vaccine increases.

We observe that as the fraction of vaccinated people increases, the total number of infected decreases, and the proportion of vaccinated among the infected also increases. As we want less people infected, media should pay more attention to the evolution of the total of infected people, rather than to the proportion of vaccinated among infected.

Let’s examine more formally the evolution of the fraction of vaccinated among infected as a function of the fraction of vaccinated . The parameters to consider are:

- The population .

- The proportion of infected people when there are no vaccines available. Its value depends on the measures taken to control the spread of the infection, so it can be different for each population.

- The efficacy of the vaccine .

The number of infected, unvaccinated people is:

While an unvaccinated individual has a probability of of being infected, a vaccinated individual will have a probability of infection . So, the number of infected, vaccinated people is:

The total number of infected people will be:

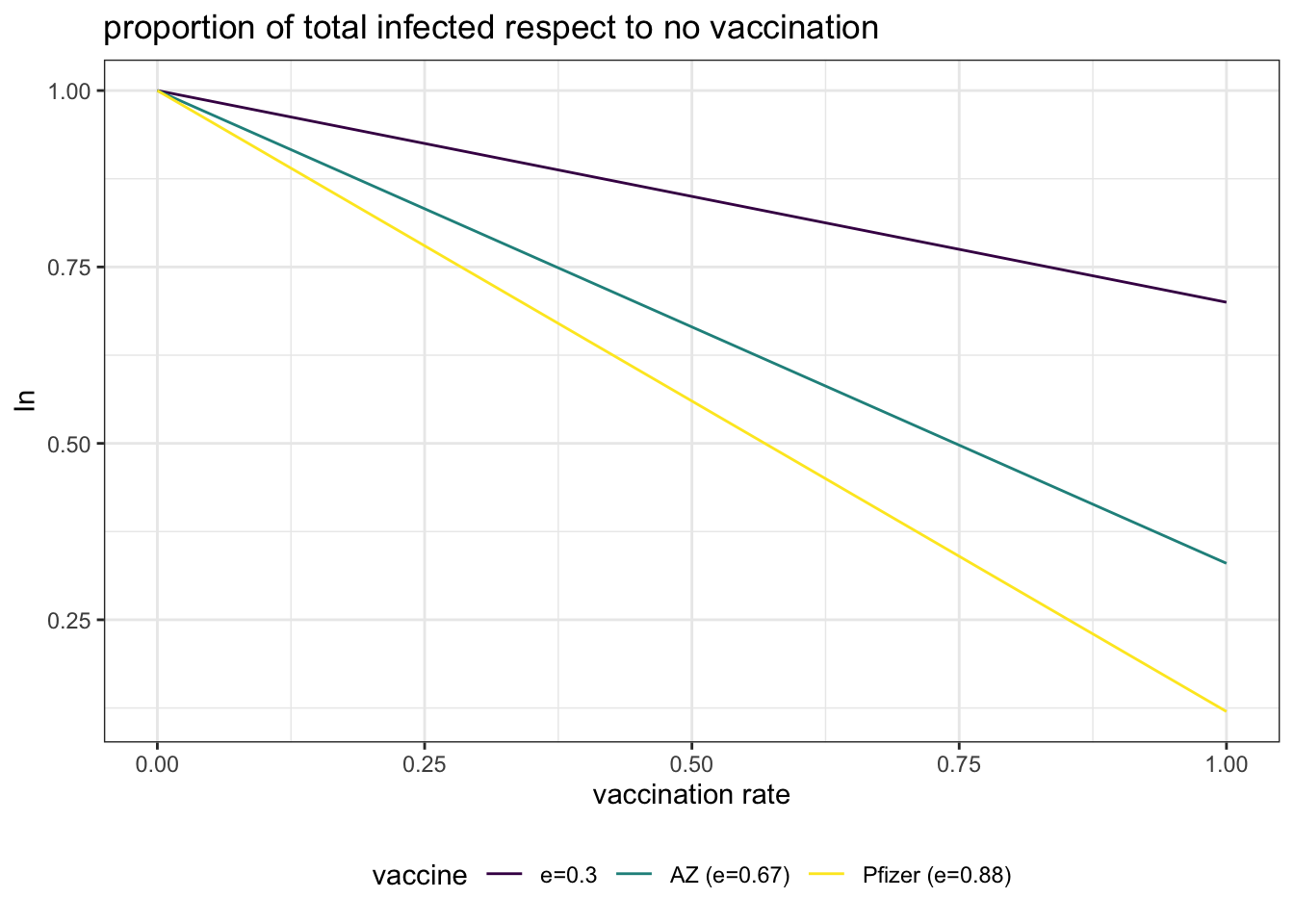

If we normalize this value with the number of infected people with no vaccines :

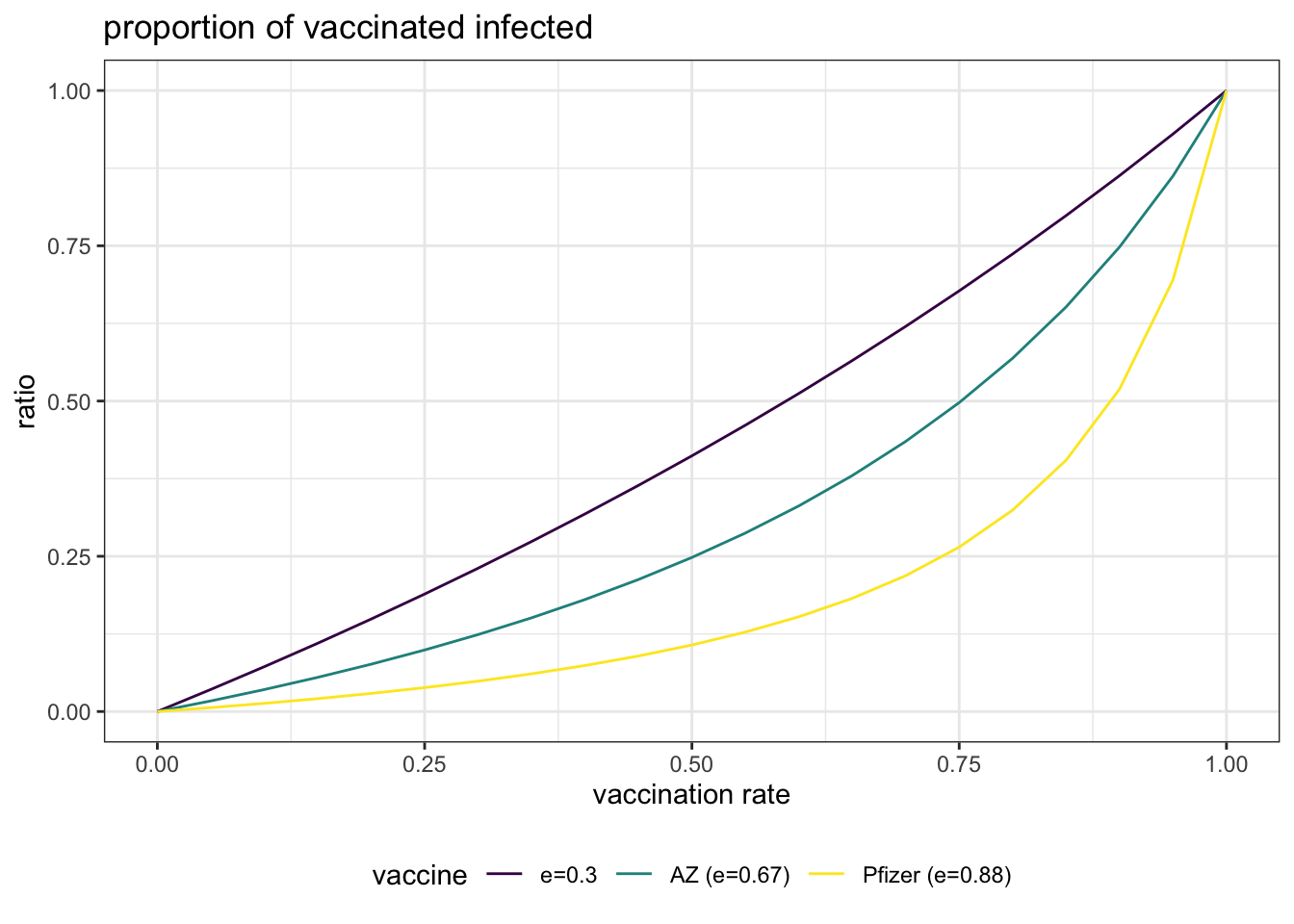

And the ratio of vaccinated and infected respect to total infected will be:

Note that if the ratio is equal to zero, and if is equal to one. This makes sense, as in the later case there are no unvaccinated people.

Let’s examine the ratio of vaccinated, infected people for the Pfizer and AZ vaccines with the delta variant ( equal to 88% and 67% respectively), together with an hypothetical vaccine of efficacy of 30% as vaccination rate grows.

IF we examine the total number of infected, we observe that the value of will decrease linearly:

Increasing the number of vaccinated people has two effects:

- reducing the number of infected people

- reducing the number of unvaccinated people.

These two effects combined make that, for high rates of vaccination, there are more vaccinated than unvaccinated people among the infected. In Spain, the 100% of individuals of 80 years or more are vaccinated. The 98.4% of 70-79 years old and 95.2% of 60-69 years old are vaccinated. These values of are high enough to observe values of larger than 0.5.

As a conclusion, we must pay attention to the evolution of total number of infected people to track the evolution of COVID-19, rather than the proportion of vaccinated people among infected.

COVID-19 and the delta variant

In this post, I have been using efficacy values for the delta variant of COVID-19. According to the CDC, the delta variant of COVID-19 is more contagious, and might cause more severe illness than previous variants in unvaccinated people. A recent study from Lopez Bernal et al. has shown that the Pfizer and Astra Zeneca vaccines have lower efficacy for the delta variant than for the alpha variant.

| vaccine | efficacy alpha | efficacy delta |

|---|---|---|

| Pfizer (BNT162b2) | 93.7% (95% CI, 91.6 to 95.3) | 88.0% (95% CI, 85.3 to 90.1) |

| Astra Zeneca (ChAdOx1) | 74.5% (95% CI, 68.4 to 79.4) | 67.0% (95% CI, 61.3 to 71.8) |

Although the efficacy of vaccines might have been reduced because of this delta variant, the dire consequences of this variant of COVID-19 for the unvaccinated make getting your vaccine the wisest choice.

References

- Lopez Bernal, J., Andrews, N., Gower, C., Gallagher, E., Simmons, R., Thelwall, S., … & Ramsay, M. (2021). Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant. New England Journal of Medicine, 385:585-594 https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2108891

- Vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and protection https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/vaccine-efficacy-effectiveness-and-protection

- Delta variant: What we know about the science https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/delta-variant.html